© Garden Cottage Nursery, 2022

Plants And Their Pollinators

Pollinators

Much as we may like to see flowers they are not there to impress us, they are designed to attract pollinators, mostly insects, to the

plant and enable the plant to sexually reproduce.

The plant provides a reward to the pollinator in the form of nectar or edible pollen and the plant benefits by being able to spread it’s

genes.

There are between 250,000 and 400,000 plant species in the world and hundreds of novel solutions to getting pollen to their

stigma.

A huge number, like the conifers did before them, rely on the wind to simply blow their pollen into another receptive plant, e.g.

grasses, hence hay fever. Being so scattergun requires you to produce loads of extra pollen. If you get something like a bee to

carry your pollen to another flower for you you save a lot or resources as you don’t need to produce as much pollen, but you

instead need to invest resources in a flower to attract pollinators to you and then offer them a reward for visiting.

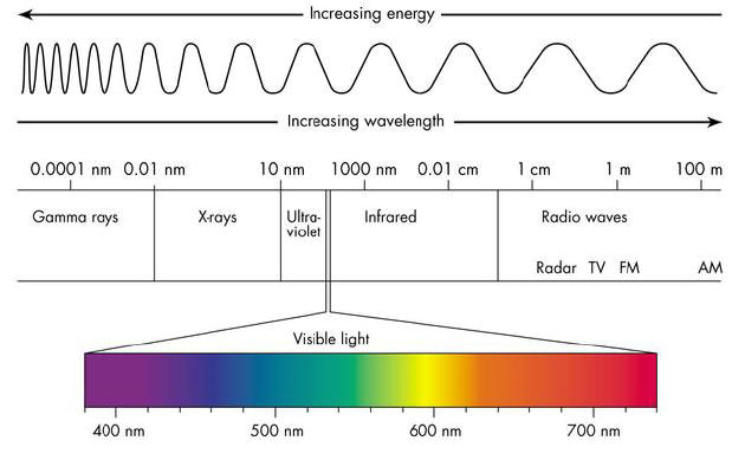

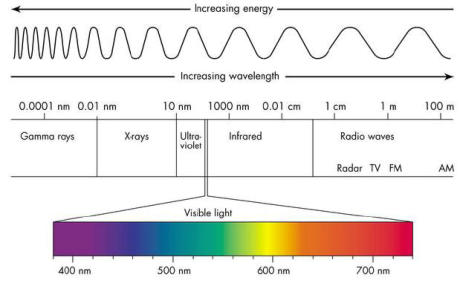

Eyes are biological sensors like radio sets tuned to certain frequencies on the electromagnetic spectrum. Radios pick up EM

frequencies between about 150 kHz and 25mHz or EM waves from around a metre long to ones a hundred or more metres long.

Visible light runs from violet at 790THz (790,000,000,000,000 Hz) / 380nm (0.000000380 m) to red at 400THz / 740nm. Our brain

assigns a meaning, i.e. colour, to photons in the visible spectrum striking our the back of our eye.

All materials are transparent and opaque to different frequencies on the EM spectrum, flesh is transparent to x-rays, bone is not,

which is useful for doctors. Plant leaves look green to us because they largely absorb blue and red light frequencies (to drive

photosynthesis) striking them from the sun and reflect the green bit in between.

Different animals are sensitive to different wavelengths of light, most insects are able to see well beyond the frequencies of visible

light (to humans) into the Ultra Violet. It is light at these higher frequencies that attract insects most, as such the colours in the

visible spectrum are not hard indicators of likely pollinators but they can still help indicate pollinator types.

So as not to exclude potential pollinators most plants take a generalist approach to attracting pollinators, not specialising too much

in morphology so as to allow as many different potential pollinators access to their flowers.

Many plants have some degree of adaptation which may favour certain types of pollinator over others. A few, particularly among

orchids, go all out via natural selection and can become committed to even a single species of pollinator in a sort of self-fulfilling-

prophecy-evolutionary-spiral of ever more specialisation and mutual reliance.

Perhaps the most frequently cited example of pollinator specialisation is the Madagascan orchid Angraecum sesquipedale which

possesses incredibly long narrow spurs to the flower at the bottom of which resides the nectar. In 1862 Charles Darwin published a

work on orchid specialisation for pollinators in which he examined this flower, after much experimentation he concluded that to

effect pollination of the flower and for the pollinator to get its nectar reward it would require a moth with a 35cm long proboscis.

Many dismissed this as fanciful at the time but then in 1903, 21 years after Darwin’s death, the moth which did the job was duly

found. You can read more about it here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angraecum_sesquipedale

Bees respond to generally showy flowers, are especially keen on flowers rich in nectar, though sometimes frequenting those

offering a reward of pollen instead of nectar. Yellow and blue flowers are particularly popular; many have markings guiding the bee

like runway lights to the reward, often this is visible only in Ultra Violet wavelengths of light. Bees are absolutely vital to our survival

in their role as pollinators for many of our food crops. Internationally bees, both wild types like our familiar bumble bees and

commercially bred honey bees are in drastic decline. There seems to be several factors combining to cause this decline including

disease, parasitism, climate change and insecticide use. By offering as many plants attractive to bees as possible in your garden

you can do your little bit to help your local bee population. Good bee plants include: Aquilegia, Brunnera, Caltha, Doronicum,

Eryngium, Fuchsia, Geranium, Hemerocallis, Iberis, Jasione, Knautia, Lamium, Monarda, Nepeta, Olearia, Primula, Quercus (oaks,

like chestnuts, which makes odd tasting honey, provide pollen rather than nectar), Rudbeckia (Rhododendron provide tons of nectar

for bees but many varieties make the bees ‘drunk’), Salvia, Thymus, Ulex, Verbascum, Weigela, Xanthorrhoea, Ypsilandra and

Zinnia. An X,Y and Z wasn’t easy to come up with!

Though moths are not major pollinators in the North of Scotland,

elsewhere they can play an important role. Hawk moths

particularly have quite a lot of flowers evolved to suit them.

Generally flowers for moths are large open, creamy or white,

often sweetly or musky scented in the evening. They are usually

pollinated on the wing and are nectar-rich to support the hawk

moths active life-style.

Checkout the fascinating symbiosis between certain species of

Yucca and the Yucca moth.

Passiflora mollissima (left) the ‘Banana Passionfruit’ frequented by heavy weight bumble & honey bees in warmer climates.

hercaceous perennial Lobelia like Lobelia x speciosa 'Fan Lachs' (right) are great sources of nectar for bees.

The epiphytic cactus Epiphyllum angulare with large musky

scented flowers that last only one night each

Butterflies prefer pink and lavender coloured flowers, often

strongly scented with long narrow tubes to allow the

butterflies to get their long tongues down to the ample

nectar.

A few good butterfly plants are: Buddleja, Calendula,

Echinops, Eutrochium, Echinacea, Hebe, Kniphofia,

Lavandula, Mentha, Sedum and Verbena.

Red Admiral butterflies on Buddleja ‘Lochinch’

There are huge numbers of flies in multitudinous varieties, there are many generalist species that take advantage of any available

food source and this makes them very frequent pollinators of flowers particularly of non-specialised flowers. Their ubiquity makes

them important pollinators in more extreme environments like alpine regions where there aren’t the range of different specialised

pollinators. Many plants also use trickery to attract to attract pollinators and particularly flies. Some flowers will produce chemicals

that mimic fly pheromones to attract male flies which will then crawl all over the flower covering themselves in pollen, the plant

hopes the fly will then go to another flower of the same species, falling for the same trick again and shed some of its pollen on the

stigmas of the second flower. Another common method of duping flies used by plants is to make a flower appear to the fly to be a

rotting animal. These flowers are often red or brown in colour and mottled and put out an irresistible scent of corrupting meat. A

great many aroids (family Araceae) are pollinated by flies, e.g. Arum, Arisaema, Dracunculus, Lysichiton and the huge and slightly

pornographic Amorphophallus titanium. The worlds largest flower is the Indonesian fly-pollinated parasite Rafflesia arnoldii, it is

sometimes charmingly called the ‘corpse plant’.

Sauromatum venosum (left) doing a convincing impersonation of a dead animal. Pericallis aurita (right)

beautiful daisy flowers armed with a strong scent of dung to help draw in flies.

Other types of insects act as pollinators in some plant species. Beetles pollinate many Magnolias, amongst the oldest of flowering

plants, as such beetles were amongst the first flower pollinators. European wasps (the normal black and yellow kind people try to

swat on sight) adore Angelica gigas and figwort (Scrophularia nodosa). Figs require certain species of small wasps to pollinate their

flowers, there was an excellent BBC Natural World documentary ‘The Queen of Trees’ on the symbiotic relationship between the

African sycamore fig and its pollinator wasp Ceratosolen arabicus and their impact on the wider environment. The producers have

put it up on youtube.

There are plants that use ants and other sorts of insects as pollinators, ones that use spiders, rodents, bats, frogs, basically if it

moves and you can stick pollen on it there is a plant somewhere that uses it as a pollinator.

© Garden Cottage Nursery, 2021

Plants And Their Pollinators

Pollinators

Much as we may like to see flowers they are not there to

impress us, they are designed to attract pollinators, mostly

insects, to the plant and enable the plant to sexually reproduce.

The plant provides a reward to the pollinator in the form of

nectar or edible pollen and the plant benefits by being able to

spread it’s genes.

There are between 250,000 and 400,000 plant species in the

world and hundreds of novel solutions to getting pollen to their

stigma.

A huge number, like the conifers did before them, rely on the

wind to simply blow their pollen into another receptive plant,

e.g. grasses, hence hay fever. Being so scattergun requires

you to produce loads of extra pollen. If you get something like a

bee to carry your pollen to another flower for you you save a lot

or resources as you don’t need to produce as much pollen, but

you instead need to invest resources in a flower to attract

pollinators to you and then offer them a reward for visiting.

Eyes are biological sensors like radio sets tuned to certain

frequencies on the electromagnetic spectrum. Radios pick up

EM frequencies between about 150 kHz and 25mHz or EM

waves from around a metre long to ones a hundred or more

metres long. Visible light runs from violet at 790THz

(790,000,000,000,000 Hz) / 380nm (0.000000380 m) to red at

400THz / 740nm. Our brain assigns a meaning, i.e. colour, to

photons in the visible spectrum striking our the back of our eye.

All materials are transparent and opaque to different

frequencies on the EM spectrum, flesh is transparent to x-rays,

bone is not, which is useful for doctors. Plant leaves look green

to us because they largely absorb blue and red light

frequencies (to drive photosynthesis) striking them from the sun

and reflect the green bit in between.

Different animals are sensitive to different wavelengths of light,

most insects are able to see well beyond the frequencies of

visible light (to humans) into the Ultra Violet. It is light at these

higher frequencies that attract insects most, as such the

colours in the visible spectrum are not hard indicators of likely

pollinators but they can still help indicate pollinator types.

So as not to exclude potential pollinators most plants take a

generalist approach to attracting pollinators, not specialising

too much in morphology so as to allow as many different

potential pollinators access to their flowers.

Many plants have some degree of adaptation which may favour

certain types of pollinator over others. A few, particularly among

orchids, go all out via natural selection and can become

committed to even a single species of pollinator in a sort of

self-fulfilling-prophecy-evolutionary-spiral of ever more

specialisation and mutual reliance.

Perhaps the most frequently cited example of pollinator

specialisation is the Madagascan orchid Angraecum

sesquipedale which possesses incredibly long narrow spurs to

the flower at the bottom of which resides the nectar. In 1862

Charles Darwin published a work on orchid specialisation for

pollinators in which he examined this flower, after much

experimentation he concluded that to effect pollination of the

flower and for the pollinator to get its nectar reward it would

require a moth with a 35cm long proboscis. Many dismissed

this as fanciful at the time but then in 1903, 21 years after

Darwin’s death, the moth which did the job was duly found.

You can read more about it here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angraecum_sesquipedale

Bees respond to generally showy flowers, are especially keen

on flowers rich in nectar, though sometimes frequenting those

offering a reward of pollen instead of nectar. Yellow and blue

flowers are particularly popular; many have markings guiding

the bee like runway lights to the reward, often this is visible

only in Ultra Violet wavelengths of light. Bees are absolutely

vital to our survival in their role as pollinators for many of our

food crops. Internationally bees, both wild types like our familiar

bumble bees and commercially bred honey bees are in drastic

decline. There seems to be several factors combining to cause

this decline including disease, parasitism, climate change and

insecticide use. By offering as many plants attractive to bees as

possible in your garden you can do your little bit to help your

local bee population. Good bee plants include: Aquilegia,

Brunnera, Caltha, Doronicum, Eryngium, Fuchsia, Geranium,

Hemerocallis, Iberis, Jasione, Knautia, Lamium, Monarda,

Nepeta, Olearia, Primula, Quercus (oaks, like chestnuts, which

makes odd tasting honey, provide pollen rather than nectar),

Rudbeckia (Rhododendron provide tons of nectar for bees but

many varieties make the bees ‘drunk’), Salvia, Thymus, Ulex,

Verbascum, Weigela, Xanthorrhoea, Ypsilandra and Zinnia. An

X,Y and Z wasn’t easy to come up with!

Though moths are not major pollinators in the North of Scotland,

elsewhere they can play an important role. Hawk moths

particularly have quite a lot of flowers evolved to suit them.

Generally flowers for moths are large open, creamy or white,

often sweetly or musky scented in the evening. They are usually

pollinated on the wing and are nectar-rich to support the hawk

moths active life-style.

Checkout the fascinating symbiosis between certain species of

Yucca and the Yucca moth.

Passiflora mollissima the ‘Banana Passionfruit’ frequented by

heavy weight bumble and honey bees in warmer climates

The epiphytic cactus Epiphyllum angulare with large musky

scented flowers that last only one night each

Butterflies prefer pink and lavender coloured flowers, often

strongly scented with long narrow tubes to allow the butterflies

to get their long tongues down to the ample nectar.

A few good butterfly plants are: Buddleja, Calendula, Echinops,

Eutrochium, Echinacea, Hebe, Kniphofia, Lavandula, Mentha,

Sedum and Verbena.

Red Admiral butterflies on Buddleja ‘Lochinch’

There are huge numbers of flies in multitudinous varieties, there

are many generalist species that take advantage of any

available food source and this makes them very frequent

pollinators of flowers particularly of non-specialised flowers.

Their ubiquity makes them important pollinators in more

extreme environments like alpine regions where there aren’t the

range of different specialised pollinators. Many plants also use

trickery to attract to attract pollinators and particularly flies.

Some flowers will produce chemicals that mimic fly pheromones

to attract male flies which will then crawl all over the flower

covering themselves in pollen, the plant hopes the fly will then

go to another flower of the same species, falling for the same

trick again and shed some of its pollen on the stigmas of the

second flower. Another common method of duping flies used by

plants is to make a flower appear to the fly to be a rotting

animal. These flowers are often red or brown in colour and

mottled and put out an irresistible scent of corrupting meat. A

great many aroids (family Araceae) are pollinated by flies, e.g.

Arum, Arisaema, Dracunculus, Lysichiton and the huge and

slightly pornographic Amorphophallus titanium. The worlds

largest flower is the Indonesian fly-pollinated parasite Rafflesia

arnoldii, it is sometimes charmingly called the ‘corpse plant’.

Sauromatum venosum (left) doing a convincing impersonation

of a dead animal. Pericallis aurita (right) beautiful daisy flowers

armed with a strong scent of dung to help draw in flies.

Other types of insects act as pollinators in some plant species.

Beetles pollinate many Magnolias, amongst the oldest of

flowering plants, as such beetles were amongst the first flower

pollinators. European wasps (the normal black and yellow kind

people try to swat on sight) adore Angelica gigas and figwort

(Scrophularia nodosa). Figs require certain species of small

wasps to pollinate their flowers, there was an excellent BBC

Natural World documentary ‘The Queen of Trees’ on the

symbiotic relationship between the African sycamore fig and its

pollinator wasp Ceratosolen arabicus and their impact on the

wider environment. The producers have put it up on youtube.

There are plants that use ants and other sorts of insects as

pollinators, ones that use spiders, rodents, bats, frogs, basically

if it moves and you can stick pollen on it there is a plant

somewhere that uses it as a pollinator.